Long before Europeans arrived, Paleo-Indians first settled North America around the end of the Ice Age, some 14,000 years ago. Since then, many Indigenous groups have made these lands home. Though the Indigenous history of the United States can often be overlooked, there are plenty of fascinating monuments to learn more about the history of our nation, many of which have stood for thousands of years. Here are 17 landmarks that delve into America’s Indigenous history.

Poverty Point National Monument – Louisiana

Nearly 2 million cubic yards of soil in northeastern Louisiana have been shaped into a natural wonder at Poverty Point. At the center of this national monument and UNESCO World Heritage Site is a 72-foot-tall mound with concentric circles around it that was constructed by hand more than 2,200 years ago. With no official records, little is known about the Indigenous peoples’ lives there, but it’s believed that some of the materials used to construct the site were brought in from as far as 800 miles away, making it as much of a human-made wonder as Stonehenge. It’s believed that the area was inhabited for about 600 years until it was mysteriously abandoned around 1100 BCE.

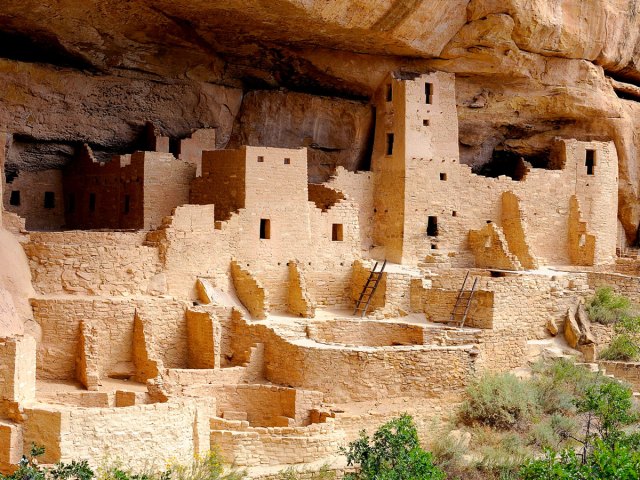

Mesa Verde National Park – Colorado

For more than 700 years, the area of Colorado that’s now Mesa Verde National Park was home to the Ancestral Puebloans. Though they had previously been nomadic, they settled in the area around 550 CE, living in pit houses built on top of mesas and into cliff recesses. Through the generations, those evolved into structures built of adobe and poles — some with as many as 50 rooms — and eventually to kivas, pueblos made of stone. But around 1200, they shifted back to living in the cliffside, into the dwellings that Mesa Verde is most known for today.

A generation or two after those canyon alcove homes were built, the population — believed to have reached several thousand — abandoned the entire area. Now the national park, which was established in 1906 by President Theodore Roosevelt to “preserve the works of man,” also protects the heritage of 26 associated tribes, including the Taos of New Mexico, Hopi of Arizona, and Ute Mountain of Colorado.

Chief Massasoit Statues – Massachusetts and Utah

Across the street and above the hill from the famous Plymouth Rock is a statue of Chief Massasoit, who lived from about 1581 to 1661 and was the leader of the Wampanoags, the Native Americans who inhabited New England long before the English arrived in 1620. He is believed to have greeted the Pilgrims, and the following year, he and 90 of his men joined them for three days of feasting, which has evolved into the Thanksgiving tradition.

The sculpture of Chief Massasoit was created by Utah artist Cyrus Dallin in 1921, and the original plaster figure given to the state in 1922. Five years later, a duplicate was funded in bronze and placed in front of the Utah State Capitol in 1959.

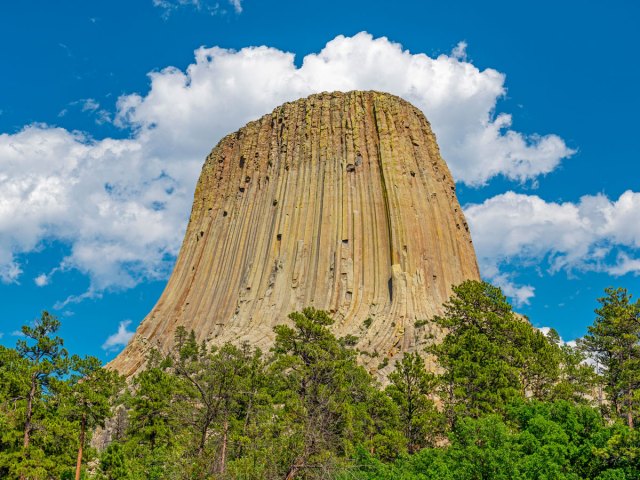

Devils Tower National Monument – Wyoming

Devils Tower, a striking natural 867-foot-tall formation rising from the prairie of the Black Hills with a flat top the size of a football field, has long been a natural wonder. Scientists believe it formed from molten rock underground which was then pushed upward by magma. The site has long been a sacred one for the Indigenous peoples of the area, and prayer offerings are still made today, marked by colorful bundles placed around the tower.

Associated tribes have given various names to the tower — Araphoes called it “Bear’s Tipi,” Kiowas named it “Tree Rock,” and Lakota — who have the most documented connections with it — gave it various names, including “Bear Lodge,” “Ghost Mountain,” and “Grey Horn Butte.” The Devils Tower name came from an 1875 scientific exploration trip, when an army commander wrote that the Native Americans called it “Bad God’s Tower,” which he translated to “Devils Tower.” However, many early maps of the area call it Bear Lodge, which is translated from one of the Lakota names, Mato Tipila. Efforts have been underway to change its name to Bear Lodge. (You may also recognize the landmark from the 1977 sci-fi film “Close Encounters of the Third Kind.”)

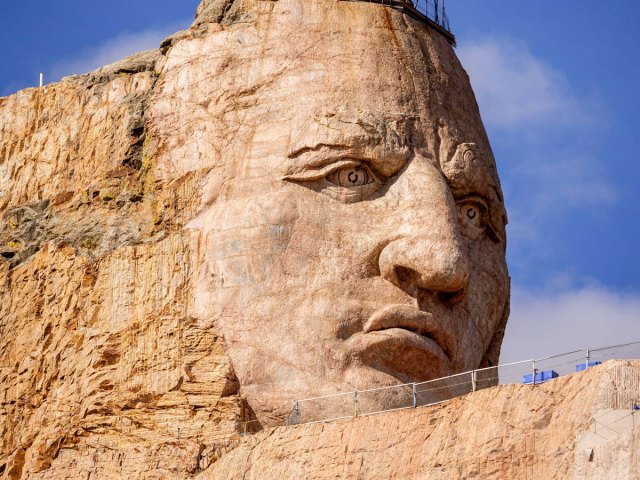

Crazy Horse Memorial – South Dakota

Also located in the Black Hills is a 6,532-foot-tall mountain that is the site of the Crazy Horse Memorial, depicting Oglala Lakota Chief Crazy Horse. It will become the world’s largest sculpture when it’s completed — but when it will be finished is the big question. The project began when Oglala Lakota Chief Henry Standing Bear invited Polish American sculptor Korczak Ziolkowski to the area in 1947 to carve a memorial for all North American Indians. The sculptor started the project in 1948, estimating it would take three decades to complete, but he passed away in 1982.

It’s still a major work in progress — the next five to ten years are scheduled to focus on Crazy Horse’s hairline, right shoulder, and left arm and hand, as well as the horse’s mane and head. Visitors can see the work in progress, as well as two museums, the Indian Museum of North America, and the Native American Educational and Cultural Center.

Hovenweep National Monument – Colorado

Connected with the nearby Mesa Verde community, the Hovenweep area traces its first human inhabitants back more than 10,000 years ago, when nomadic Paleo Indians would pass through to hunt and gather seasonally. In about 900 CE, the area started to become a more permanent home, and 300 years later, the population reached about 2,500. The remnants of six villages that were built between 1200 and 1300 are now preserved there.

Among the most impressive are the differently shaped towers constructed by the ancestral Puebloans. By the end of the 13th century, the area was abandoned, but Hovenweep (which means “deserted valley” in Ute or Paiute) has been protected as a national monument since 1923 — preserving the cultures of the Pueblo, Zuni, and Hopi peoples.

National Native American Veterans Memorial – Washington, D.C.

Opened on Veterans Day 2020, the National Native American Veterans Memorial sits on the grounds of the capital’s National Museum of the American Indian. Selected from more than 120 entries, the Warriors’ Circle of Honor design is the work of self-taught artist Harvey Pratt of the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes of Oklahoma, who is a Vietnam War veteran himself.

The memorial’s stainless steel circle sits on a stone drum, symbolizing a sacred circle and the cycles of time and life. Water flows out from the drum, while fire can be lit for ceremonies. The inclusive memorial honors American Indian, Alaska native, and Native Hawaiian veterans — and will be formally dedicated in an on-site ceremony on Veterans Day 2022.

Indian Memorial at Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument – Montana

The decades-long clash between Native Americans and settlers of European descent came to a climax on June 25 and 26, 1876. At the Battle of Little Bighorn, the Lakota, Cheyenne, and Arapahos defeated the 12 companies of the U.S. Army’s Seventh Cavalry. Though the battlefield became a national cemetery in 1879 and a memorial was built on Last Stand Hill in 1881, most of the bodies of the Native Americans were removed and buried following their traditions — and no memorial existed in their honor.

In 1991, Congress changed the name of the site from its previous name, Custer Battlefield National Monument, to Little Bighorn Battlefield to acknowledge the Native Americans who died there, and also ordered the construction of the Indian memorial, which was dedicated in 2003 with the theme “Peace Through Unity.”

Ocmulgee Mounds – Georgia

Human settlement in central Georgia dates back nearly 17,000 years ago to the Ice Age, when nomadic Paleo Indians settled in the area. Around 1000 BCE, small villages formed, but it wasn’t until 900 CE that a society emerged known as the Mississippans, who built the site’s trademark Ocmulgee Mounds out of dirt and clay.

Among the circular earthen structures are temple mounds, a cornfield mound, and a funeral mound. The importance of the Indigenous site is evidenced by the fact that the area is on track to becoming Georgia’s first national park, possibly as soon as next year. Visitors can duck inside a re-created earthlodge for a taste of what life was like in the mound, which still has sections of the original 1015 CE floor.

Hopewell Culture National Historical Park – Ohio

Earthen mounds are also found in Ohio’s Hopewell Culture National Historical Park. These were built from 200 BCE to 500 CE, and are believed to have been used for everything from funerals to feasts, with the Hopewell peoples arranging them in circles, squares, and octagons. The 1,800-acre park has six complexes, including High Bank Works, Hopeton Earthworks, Hopewell Mound Group, Mound City Group, Seip Earthworks, and Spruce Hill Earthworks. Some of the mounds stretch as wide as 1,000 feet.

Montezuma Castle National Monument – Arizona

The five-floor, 20-room apartment complex built into the side of the limestone cliff in Arizona’s Cape Verde has long intrigued visitors as one of the most well-preserved prehistoric cliffs in the country. Estimated to have been built between 1100 and 1350 CE, the site is named Montezuma Castle, which comes from the Aztec emperor — even though it seems historically unlikely that he ever came to the area.

Now it’s more widely believed to have been the home of the pre-Columbian Sinagua peoples, who left the region in the 15th century. As one of the nation’s first national monuments dedicated in 1906, President Roosevelt said it was a place of great “ethnological value and scientific interest.”

Casa Grande Ruins National Monument – Arizona

It takes quite a monument to become the nation’s first archeological preserve, and Casa Grande Ruins National Monument had all the right qualifications when it was dedicated in 1892. As the largest known structure built by the Gila Valley’s Hohokam tribe (who lived in the region since 5550 BCE), Casa Grande — which translates to “Great House” — was built in the 14th century using 3,000 tons of caliche soil. The durable structure has four-foot-thick walls at the bottom and Juniper pine and fir tree timbers as support. Also preserved in the area are remnants of the tribe’s farming community, dating from 1150 to 1350.

Trail of Tears National Historic Trail – Georgia to Oklahoma

The Indian Removal Act in 1830 forced major tribes — including the Choctaws, Muscogee Creeks, Seminoles, and Chickasaw — to leave their homelands and move west of the Mississpippi to what is now Oklahoma. After initially resisting, the Native Americans eventually were forced to give in and escorted to their new homes by the U.S. Army troops in what was called the Trail of Tears. In total, 16,000 Cherokees alone were taken from Tennessee, Alabama, North Carolina, and Georgia.

Today, a 5,043-mile pathway through nine states commemorates the suffering — as well as the resilience — along that journey, with sites that include the Museum of the Cherokee Indian in Cherokee, North Carolina; the Trail of Tears Commemorative Park in Hopkinsville, Kentucky; and the Cherokee Heritage Center in Tahlequah, Oklahoma.

Petroglyph National Monument – New Mexico

All over this Albuquerque area are symbols and designs carved into volcanic rock, making it one of the biggest petroglyph (or rock carving) sites on the continent. Thought to have been created between 400 to 700 CE, Petroglyph National Monument features three short trails with hundreds of carvings along the way.

These include the Boca Negra Canyon with 100 carvings, the 2.2-mile loop of Rinconada Canyon with 300 of them, and the 1.5-mile Piedras Marcadas trail with a whopping 400 petroglyphs. The symbols are believed to have spiritual meaning — about 90% of them are the work of the ancestors of the Pueblos, who have lived in the Rio Grande Valley since 500 CE.

Sitka National Historic Park – Alaska

Located in southeastern Alaska on a forested island near the mouth of the Indian River, the Sitka National Historic Park commemorates the histories of two very distinct cultures: the Tingit people and Russian American traders. Both lived and thrived in the area, but tensions came to a head in 1804 at the Battle of Sitka, with the Russians prevailing. The battle site is now memorialized with a trail lined with totem poles of the Tlingit and Haida people along the way.

Canyons of the Ancients National Monument – Colorado

In the southwestern corner of Colorado, along the Dolores River, is the nation’s highest concentration of archaeological sites. Canyons of the Ancients National Monument covers a whopping 176,000 acres; among them are 8,300 sites that feature kivas, villages, field houses, cliff homes, stone carvings, and sweat lodges — showcasing elements of what life was like for the Ancestral Puebloans (also called Anasazi), Ute, and Navajo cultures. The earliest inhabitants of the area go back 10,000 years. The monument also features a research collection with more than 3 million artifacts, as well as two archaeological sites that date to the 12th century.

Chumash Painted Cave State Historic Park – California

While the meaning of these cave paintings has been lost over the years, the art in the Chumash Painted Cave are among some of the best preserved works of the Chumash people — who lived along the California coast, both on the mainland and on three of the Channel Islands. The small cave’s imagery, believed to be from the 1600s (or even earlier), is accessible by ascending the steep pathway to the mouth of the cave, where the images are protected by an iron gate.

More from our network

Daily Passport is part of Optimism, which publishes content that uplifts, informs, and inspires.